After Leonardo

After Leonardo

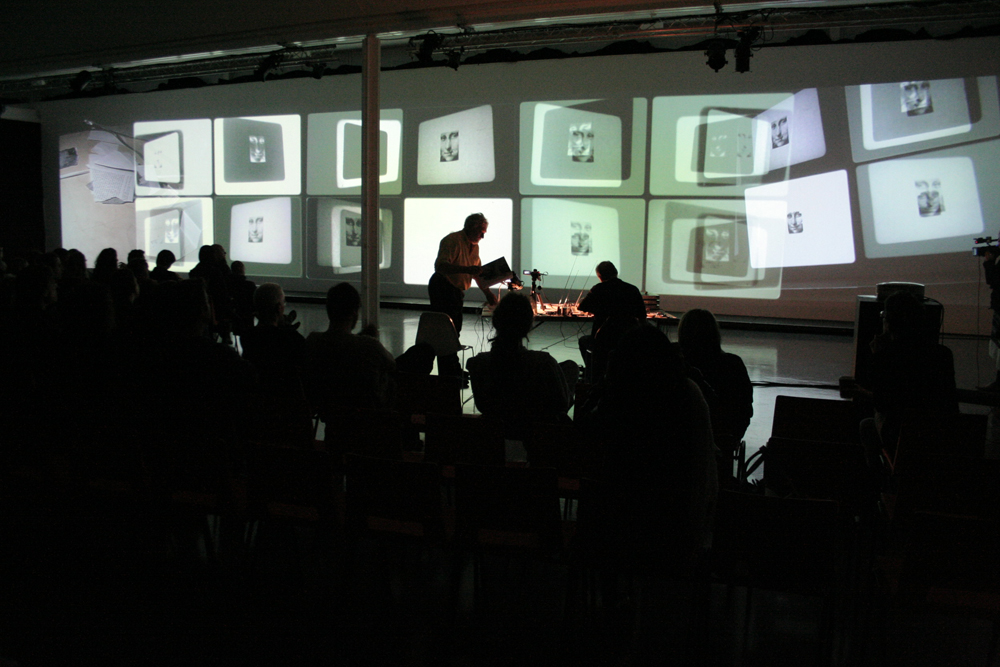

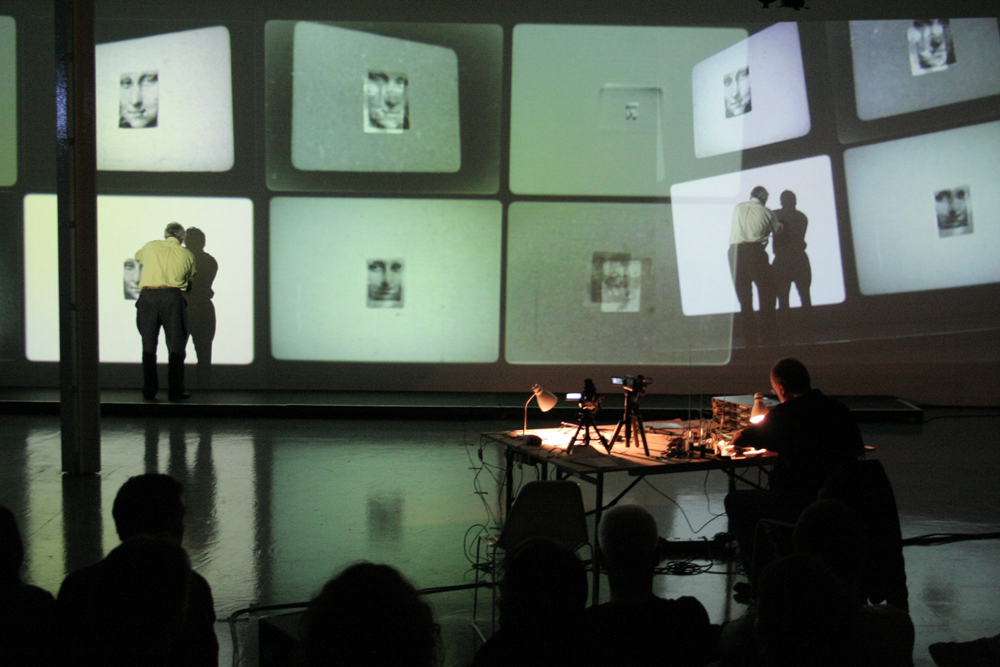

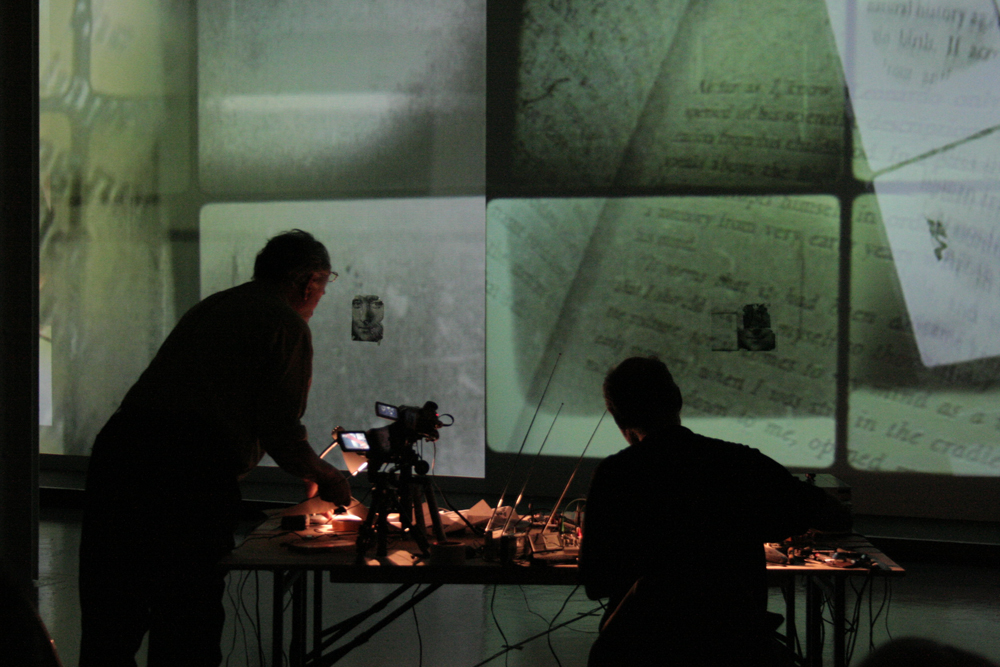

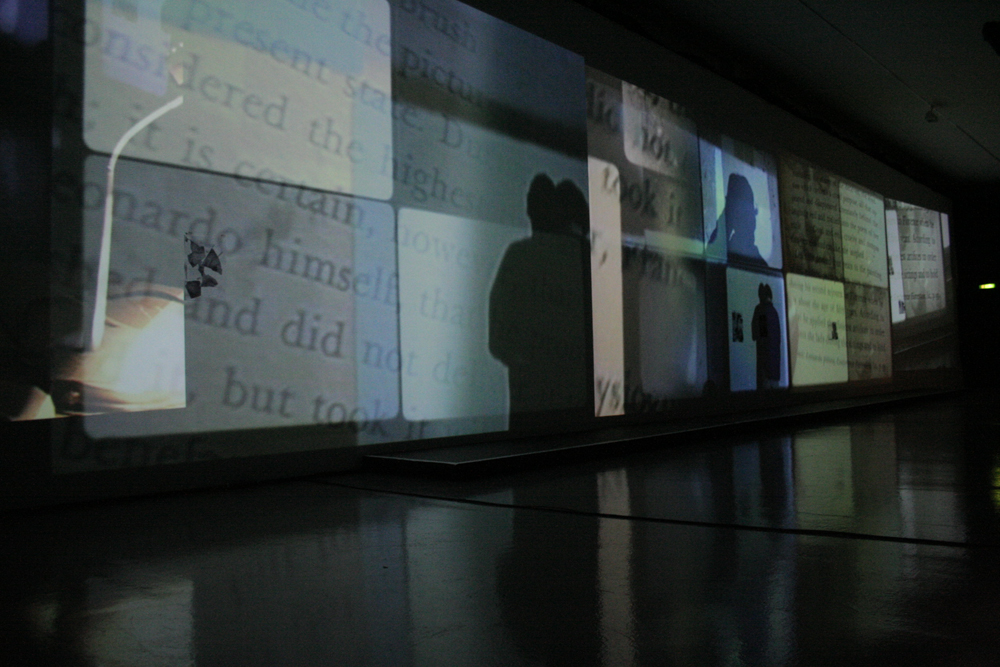

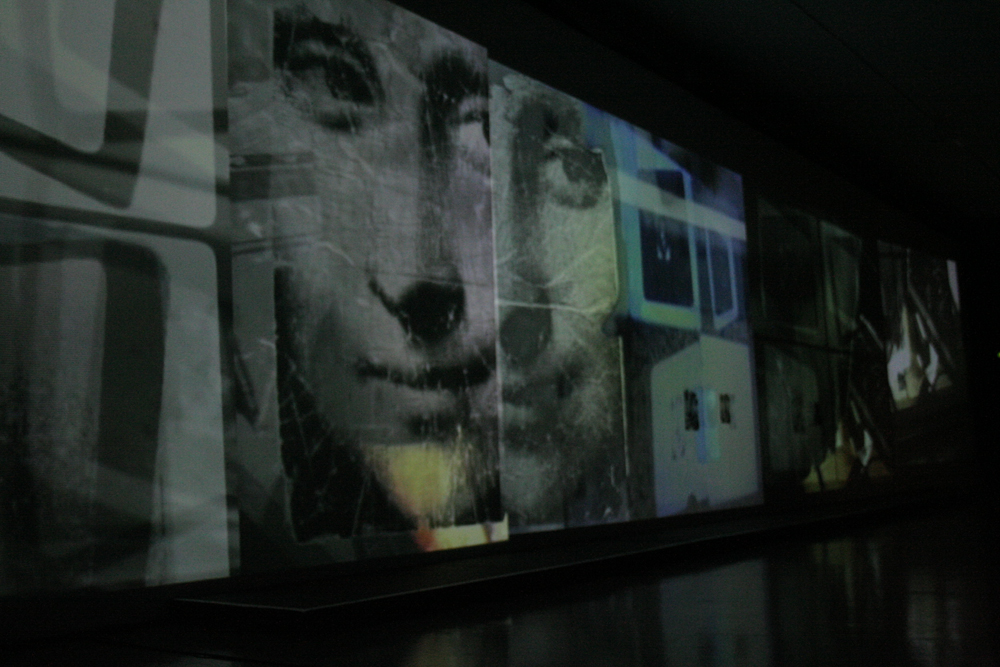

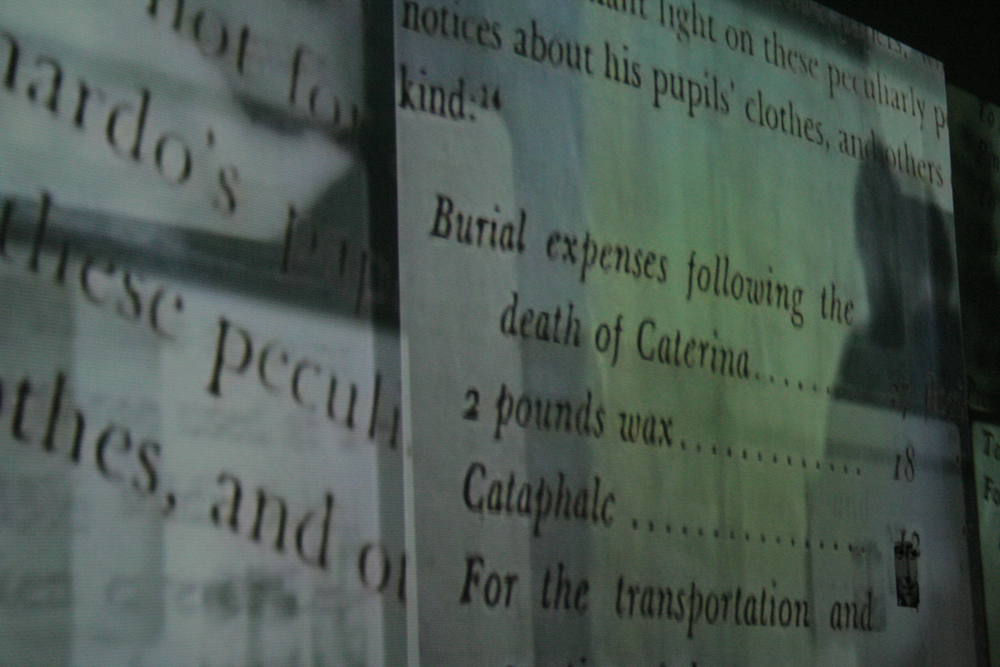

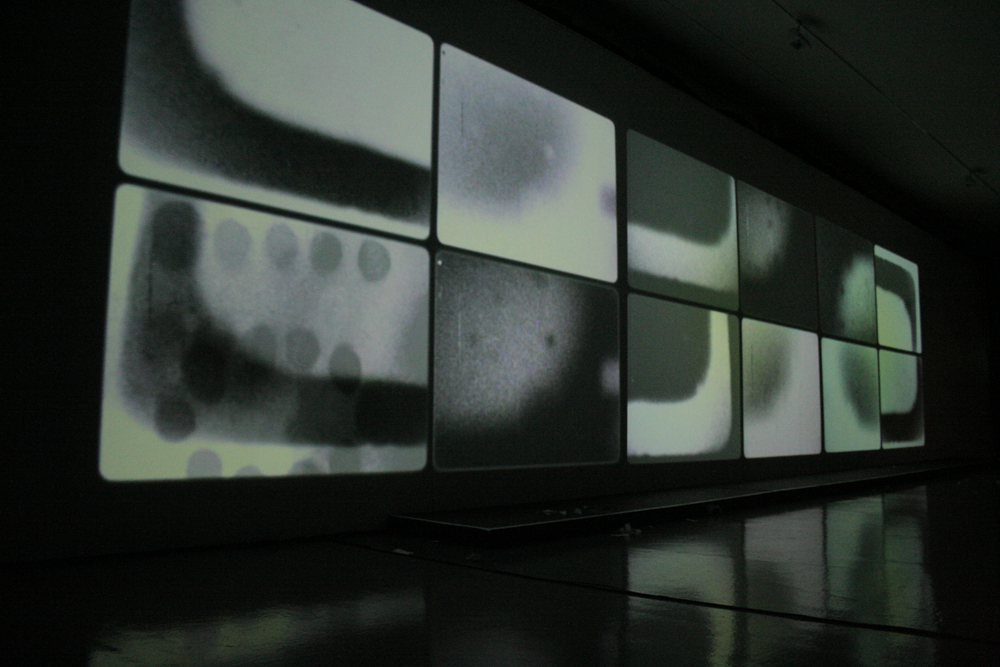

This performance restages and transforms Malcolm’s 1973 work After Leonardo. A black and white close up of the Mona Lisa, (purloined from a magazine, cracked and torn), is filmed, re-filmed, re-filmed and re-filmed again until the cracks and tears become symbols of the passage of time and the re-filming and multiple re-projecting situates these images again in time and space.

ReadMalcolm Le Grice is one of the UK’s great experimental filmmakers, who through the 60’s and 70’s created films and performances that reshaped the material properties of film (light, time, process) to create an anti-narrative, non-symbolist art form with a whole clutch of new potentials: think Robert Rauschenberg, Ornette Coleman, John Cage rather than Godard and the like.

Here’s a thing. Let’s pay attention to two of Malcolm’s main artistic challenges: to the significance of cinema/ photography as a retrospective, material, reflective process and to the prevalent commodity based nature of art – which we think any decent minded person would recognise is an extremely narrow way of looking at human creativity.

This performance asks a few interesting and enjoyable questions:

Q1: Can film explore time and, to quote Malcolm directly, “the exploration of the continuing puzzle about the passage of time – the inadequacy of the arbitrary passing moment and the impossibility of permanence”?

Q2: What’s the difference between the real object (the torn photograph), and it’s representation – the photocopies of it on the floor and the re-filmed image projected on the screen. Is film light or is it a physical, material process; is it a real thing, or representation, or both?

Q3: What does authenticity/ authorship really mean? A good quote here from Hollis Frampton explains it better than I could: “If it is impossible to own the Mona Lisa (in fact, it is inadvisable to, since presumably the responsibility is much too large, whether you like the thing or not), nevertheless it is possible to have for free, if you are willing to dispense with its unique aura, with the specific fact of that specific mass of pigment on that particular panel guided by the fine Italian hand of that particular aura-ridden artist—if you are able to dispense with that, if you can give it up, then you can have something like the Mona Lisa. You can have it, so to speak, for nothing, or next to nothing. Its cost is low. You don’t have to have a palace to house it in; then you don’t have to heat the palace; then you don’t have to hire armed guards to defend it. And we can ask ourselves whether it’s worth it or not to dispense with that aura in the interest of the likeness.”

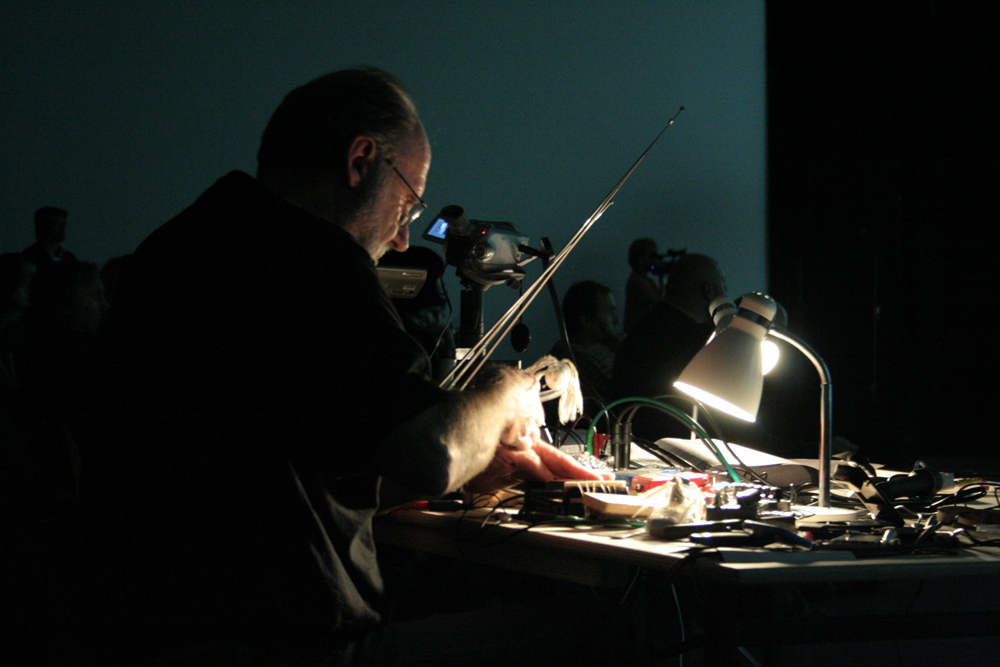

Keith Rowe, trained as a painter, is one of the UK’s great experimental musicians. By laying his guitar on it’s back and starting to play it with unexpected materials (radios, fans, knives) he gave up a good deal of control over his instrument, or more accurately, opened it up to chance, in which he could still make decisions. He is one of the key progenitors of electro-acoustic improvisation, and his approach to between-ness as a way of creating collaborative music – the push and pull between different people/ poles marks him out as a deeply considered improviser, interested in the social space created by performance – his instrument, the room, you, the interconnectedness of these things here, right now.

Documentation

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre

▴ Credit: Bryony McIntyre