Short Film Programme 1: Retrospective

Short Film Programme 1: Retrospective

Our two film programmes feature works that blur the boundaries between music and film from artists who cross and redefine those long held divisions. This programme focuses on the forebearers of filmic and musical innovation over the last 70 years. Below are a selection of links to some of the films in the programme.

Study # 6, Dir. Oskar Fischinger, USA, 1930, 16mm, 2 mins

Fishinger is regarded as the grandfather of synchronous animation and worked solidly in the 30’s and 40’s creating and innovating films and processes combining rhythm and image. His work has inspired several generations of artists, including many festured in these programmes. “The music is a fandango, ‘Los Verderones’ by Jacinto Guerrero, and the figures truly dance to the catchy rhythms, but beyond the barest requirements of choreography, there are two consistent patterns of interwoven imagery – one of flying objects in the warping currents of space (either inner or outer), and the second of the eye as a center of focus – half target, half mandala giving off waves of vibrations.” Dr. William Moritz, Film Culture

Film Exercises 1-4, Dir. John & James Whitney, US, 1940-1945, 16mm, 12 mins

This piece won top prize at the First International Experimental Film Competition in Belgium 1949; the film had an original score that was written directly onto the soundtrack area of the 16mm film through a system of pendulums that the brothers had devised. The piece uses cutouts on the film, which allows points and shapes of light to pass through the film as well as be subjected to cellophane coloured gels. The Whitney’s wanted to create a dialog between “the voices of light and tone.” Their early experiments in film and the development of sound techniques lead toward this end, feeling that music was an integral part of the visual experience and that the combination had a long history in man’s primitive development and was part of the essence of life. “Painting and song share the earliest relationship in cave societies.” His theories “On the complementarity of Music and Visual Art” were explained in John’s book, Digital Harmony.

Ereni, Dir. Hy Hirsch, US, 1953, 16mm, 7 mins

Hirsch constructed kaleidoscopically beautiful films that had no parallels or precedents in the arts. His films developed a masterful mix of sound and image via oscillascope electronics and optical printing synchronized and rapidly edited to his home-made recordings of jazz and Afro-Caribbean music. The film was created by running black and white film transcriptions of oscilloscope patterns through several passes on the optical printer using superimposition and colour filters. He was an influential figure of the West Coast film scene and manifested himself in front of, and behind, the camera for films by Sidney Peterson, Harry Smith, Jordan Belson and others.

Colour Cry, Dir. Len Lye, US, 1959, 16mm, 3 mins

Inspired by Man Ray’s ‘rayogram’ experiments, Lye discovered a whole range of new applications for this process and created the most elaborate ‘shadowcast’ film ever made. Strips of 16 mm film were laid out in a dark room, covered with stencils, colour gels, and objects such as fabrics, string and saw blades, and then exposed. The complex textures and shapes he creates reflect his masterful sense of abstract movement and pure colour. The music interacts directly with the visuals; the film initially being based on a Sonny Terry piece called Fox Hunt “All of a sudden it hit me – If there was such a thing as composing music, there could be such a thing as composing motion.” Len Lye

Allures, Dir. Jordan Belson, US, 1961,16mm, 7 mins

“I think of Allures as a combination of molecular structures and astronomical events mixed with subconscious and subjective phenomena – all happening simultaneously. The beginning is almost purely sensual, the end perhaps totally nonmaterial. It seems to move from matter to spirit in some way. Oskar Fischinger had been experimenting with spatial dimensions, but Allures seemed to be outer space rather than earth space. After working with some very sophisticated equipment in the Vortex Concerts, I learned the effectiveness of something as simple as fading in and out very slowly.” Jordan Belson

Junk, Dir. Takahiko Iimura, Japan, 1962, 16mm, 12 mins

Takahiko Iimura takes a very formal and constructivist approach to his work and here deploys a powerful soundtrack by Takehisa Kosugi whose foreboding tone reflects the tone of the images portrayed. “It’s a mixture of [dead]animals, pieces of [broken] furniture, industrial waste, kids playing. I didn’t have in mind any of the kind of historical perspective, nor was I trying to make an ecological statement. I was showing the new landscape of our civilization. My point of view was animistic. I tried to revive those dead animals metaphorically and to give the junk new life.” Takahiko Iimura

Synchromy, Dir. Norman McLaren, UK/Canada, 1971, 16mm, 7 mins

Scottish born animator Norman McLaren specialised in radical short animations, feeding off everyone from Mondrian to the surrealists, and encompassed a huge variety of techniques. Here he has created an experience which enables the viewer to ‘see’ music. Colours move and pulsate; shapes stretch and collide, vibrate and recede in exciting succession. The images actually create the sound, because, for all its lively beat and complicated composition, the music is made without instruments as the same block design on the optical portion of the film has been stamped onto the soundtrack of the film stock.

YYAA, Dir. Wojciech Bruszewski, Poland, 1973, 16mm, 3 mins

“The author of the film / seen on the screen / screams: yyyy… Four sources of light constituting lighting are switched by lottery, by an electronic device, within the bounds of chance from 0 to 8 seconds. In any moment of the film only one of the four lamps casts light on the author. Each of the four directions of lighting has its equivalent in a different modulation of the author’s voice. The modulation changes synchronically with the change of lighting. The film technique provides the author with a five-minute long exhalation.” Wojciech Bruszewski

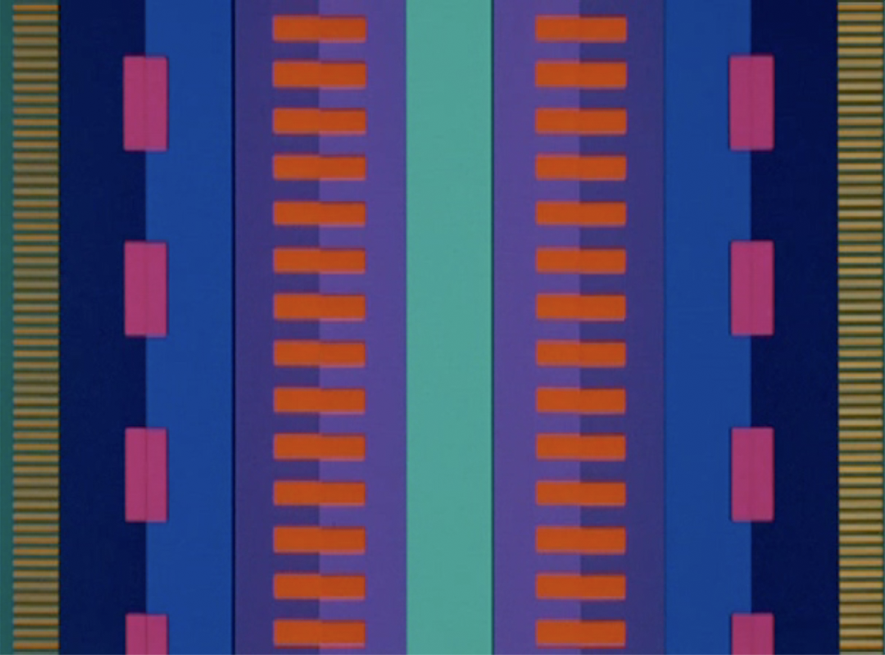

Dresden Dynamo, Dir. Lis Rhodes, UK, 1974, 16mm, 5 mins

Lis Rhodes’s Dresden Dynamo extends animated blue-magenta op-art grids into the unseen optical soundtrack. The image becomes translated into electroshock bursts of rhythmic fuzz. The result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film, the film explores how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is read by the optical sound equipment. The final print is achieved after three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer, colour added with filters on the final run. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially flat, graphic, raw material without sequence or crescendos.

Soundtrack, Dir. Guy Sherwin, UK, 1977, 16mm, 9 mins

“A continuous take through the open window of a train travelling at high speed. The camera points at right angles to the direction of travel and the area framed is from the skyline to the rails immediately below the train. By using a technique that translates the image into optical sound, these horizontal divisions create the synchronised soundtrack to the film. Here distance (perspective) affects pitch, and tonality affects volume. Buildings, objects, trains, passing through the picture area, register simultaneously on the soundtrack. As the train passes through the tunnels the screen goes black and the soundtrack cuts out, signifying to most people a break in filming, which was not the case.” Guy Sherwin

Calculated Movements, Dir. Larry Cuba, US, 1985, 16mm, 6 mins

“A choreographed sequence of graphic events constructed from simple elements repeated and combined in a hierarchical structure. The simplest element is a linear ribbon-like figure, that appears, follows a path across the screen and then disappears. The next level up in the hierarchy is an animating geometric form composed of multiple copies of the ribbon figure shifted in time and space. At this level the copies are spread out into a two-dimensional symmetry pattern or shifted out of phase for a follow-the-leader type effect, or a combination of the two. The highest level is the sequential arrangement of these graphic events into a score that describes the composition from beginning to end.” Larry Cuba

Moiré, Dir. Livinus & Jeep Van de Bundt, The Netherlands, 1975, Beta SP, 6 mins

“Video graphics – the ultimate pictorial art is Moiré’s central statement. It is a work by Livinus, the first Dutch video artist, with electronic music by his son Jeep. Livinus did not judge the possibilities of video as a medium from within the context of the institute of television and its frames of reference, but rather for its own specific visual potential. His aim was to create electronic paintings of light, movement and sound. So he built himself an image synthesizer and generator. Livinus added a new and electronically-determined dimension to the aesthetics of Fine Art’s static image. By being consciously neither narrative nor figurative – qualities that have long been appropriated by television, Moiré is an abstract rhythmic video painting with no fixed form or colour. The image changes with the beat of the music.” Montevideo

Below are some online links which you can use for reference. To see the films in their original glory, check with the distributors of the films for their terms and conditions.

Documentation

Artists