Declarative Mode (1976 – 1977)

Declarative Mode (1976 – 1977)

Declaritive mode is one of the most musical of silent experimental films, rapid-fire colour bursts thrumming on your retina in a visual approximation of musical harmony and overtone structures.

ReadPaul Sharits is one of our all time heroes, (especially in the context of KYTN) and one of the great artist filmmakers of the 20th Century. He studied music as a child and painting at art school but moved into making films in an attempt to tackle the discontinuities betweens seeing and hearing. Achieving something that approaches musical harmony, or overtones seemed almost impossible in paint, but given the technical and temporal use of persistence of vision in film, a lot more achievable. The results are some of the most demanding, exciting and emotionally and conceptually rewarding films of their time.

Declarative Mode falls in the second period of his work with musical impetus’: the first period (including Ray Gun Virus, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G etc.) worked with musical ideas of rhythm, the second period, with filmic approaches to harmony and overtone. Sharits describes Declarative Mode, in which two 16mm projections fire off rapid solid frames of single colour, superimposed on to of each other thus; “yes, there was a rhythmic phrase (in Beethoven’s 7th Symphony) that I used as a kind of motif that I came back to over and over again in various ways in Declarative Mode. I don’t mean that the whole film stemmed from that musical phrase. What I mean is that it had meaning to me. It is a very emphatic, declarative phrase and so I transposed it into colour phrases and used it in the film. If a note was sustained for a second and then the next note was sustained for half a second and the next note was, let’s say, a quarter of a second, then the pattern at that moment in the film would have that same meter.”

In Declarative Mode’s machine gun bursts of chromatic phrases, inspired by music, Sharits explores persistence of vision – the trick of the eye that allows film to kid us into thinking that it’s a real, living, moving thing, and not a series of still images printed on a physical strip of celluloid or polyester. The eye should not be able to see 24 images a second, and so blurs them together into a movement. Yet at the same time, you do see every frame, it happens there in front of you and if one were to be removed, you may well notice the difference. When we talk about sound, we say that it is the overtones of a frequency that give the sound colour, it’s rough edges, it’s timbre, it’s emotion. Sharits fuses successive images (24 of them every second) of solid colour together in time and in the eye to approach musical ideas of harmony and overtone. It is an intensely musical work, yet silent. We might invite you to use earplugs to emphasise the point.

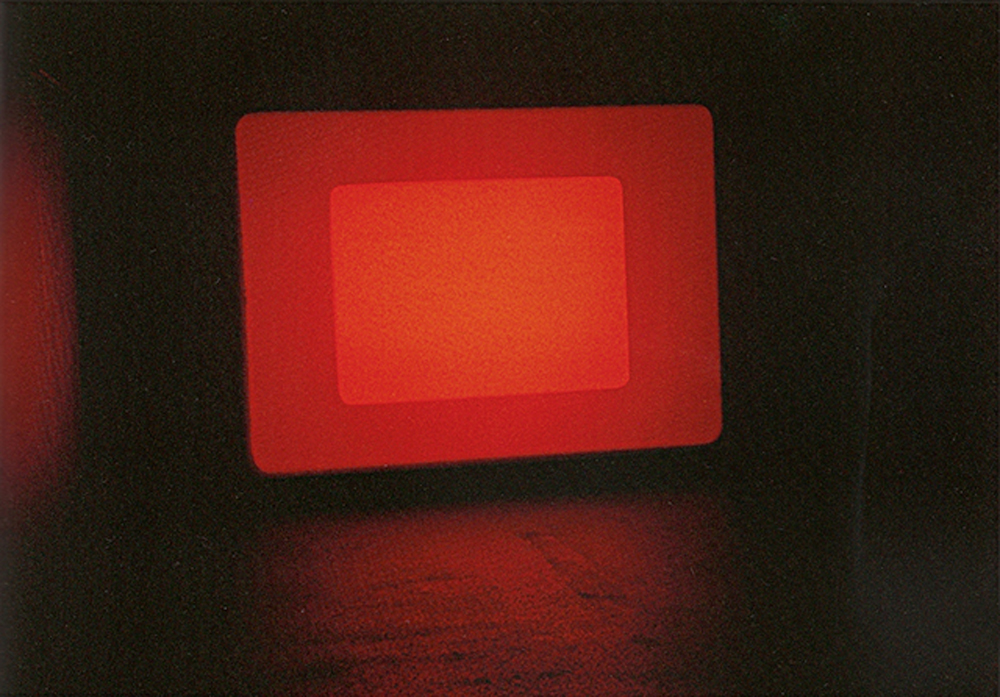

“Projection Instructions: 1. place 2 projectors close, side by side; do not load film yet. 2. turn on bulbs and find less intense bulb – use that faint bulb for the inner image (it is important that the inner image be dimmer; if necessary put a neutral filter of about 1 stop in front of lens). 3. you MUST HAVE AT LEAST ONE ZOOM LENS, so that one image can be put inside the other (the precise proportion is shown in a drawing accompanying the prints); another way of doing this is to move one projector forward until the right size is reached – but this cannot be done in a projection booth because there is not enough space. 4. make sure that inner rectangle is precisely placed so that the top and bottom borders and the sides are exactly equal – there should be absolutely no keystoning – this is of IMPORTANCE. 5. thread film and go to the punch mark on each reel. 6.ADVANCE THE FOOTAGE FOR THE INNER SCREEN 24 frames AHEAD OF THE REEL FOR THE EXTERIOR IMAGE – THIS SLIGHT OUT-OF-SYNC IS CRUCIAL TO THE EFFECT OF THE FILM. 7. start both projectors at the exact same instant. 8. FOCUS BOTH PROJECTIONS ON THEIR EDGES – the sharpness of the edges is also crucial.” (Paul Sharits)